Religion in Germany

Religion in Germany (2023 estimate)[1]

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from the fifth century onwards. The area became fully Christianized by the time of Charlemagne in the eighth and ninth century. After the Reformation started by Martin Luther in the early 16th century, many people left the Catholic Church and became Protestant, mainly Lutheran and Calvinist. In the 17th and 18th centuries, German cities also became hubs of heretical and sometimes anti-religious freethinking, challenging the influence of religion and contributing to the spread of secular thinking about morality across Germany and Europe.[2]

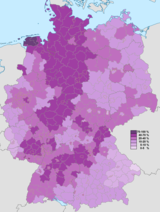

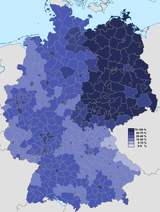

In 2023, around 48% of the population were Christians, among them 46% members of the two large Christian churches.[1][3] About half of Christians in Germany are Catholics, mostly Roman Catholics; Catholicism is stronger in the southern and the western part of the country. About half belongs to the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD) predominant in the northern regions, and the rest to several small Christian denominations such as the Union of Evangelical Free Churches in Germany, the Eastern Orthodox Church or the Jehovah's Witnesses.[4][5] Estimations for the percentage of Muslims vary between 4.6%[3] and 6.7%,[6][7] while much smaller religions include Buddhism, Judaism, Hinduism and Yazidism.[5] The rest of the population is not affiliated with any church, and many are atheist, agnostic, or otherwise irreligious.[4] 60% of German residents say that they believe there is a God, 9% say that they believe there is a higher power or spiritual force and 27% say that they do not believe there is a God, higher power or spiritual force.[8] In another survey, 44% said that they believe there is a God, 25% said that they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force and 27% said that they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force.[9] 35% of residents identify with their religion or belief.[10]

Religion in Germany (2023 Estimate)[1]

Nearly half of Germans have no religion. Demographics of religion in Germany vary greatly by region and age, with sharp divides that reflect both the country's history as an Enlightenment hub and its later experiences with post-war communism. Non-religious people typically represent the majority in Germany's major cities, including Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Munich and Cologne, as well as in the eastern states which used to be East Germany between 1949 and 1990.[11] By contrast, rural areas of the western states of what in the same period used to be West Germany are more religious, and some rural areas are highly religious.[12]

History

[edit]Paganism and Roman settlement (1000 BC–300 AD)

[edit]

Ancient Germanic paganism was a polytheistic religion practised in prehistoric Germany and Scandinavia, as well as Roman territories of Germania by the first century AD. It had a pantheon of deities that included Donar/Thunar, Wuotan/Wodan, Frouwa/Frua, Balder/Phol/Baldag, and others shared with northern Germanic paganism.[13] Celtic paganism and later Gallo-Roman syntheses were instead practised in western and southern parts of modern Germany, while Slavic paganism was practised in the east.

Late Roman and Carolingian eras (300–1000)

[edit]In the territories of Germany under the control of the Roman Empire (the provinces Raetia, Germania Superior and Germania Inferior), early Christianity was introduced and began to flourish after the fourth century. Although pagan Roman temples existed beforehand, Christian religious structures were soon built, such as the Aula Palatina in Trier (then the capital of the Roman province Gallia Belgica), completed during the reign of Roman emperor Constantine I (306–337).[14]

During the Carolingian period, Christianity spread throughout Germany, particularly during the reign of Charlemagne (r. 768–814). Religious structures built during the Carolingian period include the Palatine Chapel, Aachen, a surviving component of the Palace of Aachen built by architect Odo of Metz during the reign of Charlemagne.[15]

Pre-Reformation period (1000–1517)

[edit]Territories of the present-day Germany, like much of Europe, were entirely Roman Catholic with religious break-offs being suppressed by both the Papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor.

Reformation, Counter-Reformation and the Thirty Years' War (1517–1648)

[edit]

Roman Catholicism was the sole established religion in the Holy Roman Empire until the advent of the Protestant Reformation changed this drastically. In the early 16th century abuses (such as selling indulgences in the Catholic Church) occasioned much discontent, and a general desire for reform emerged. In 1517 the Reformation began with the publication of Martin Luther's 95 Theses detailing 95 assertions which Luther believed showed corruption and misguidance within the Catholic Church. The Reformation demonstrated Luther's disagreement both with the way in which the higher clergy used and abused power, and with the very idea of a papacy. In 1521 the Diet of Worms outlawed Luther, but the Reformation spread rapidly.[16] Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German, establishing the basis of the modern German language. A curious fact is that Luther spoke a dialect which had minor importance in the German language of that time. After the publication of his Bible translation, his dialect evolved into what is now standard modern German.

With the protestation of the Lutheran princes at the Imperial Diet of Speyer (1529) and rejection of the Lutheran "Augsburg Confession" at the Diet of Augsburg (1530), a separate Lutheran church emerged.[2]

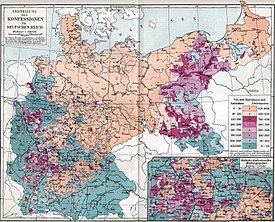

From 1545 the Counter-Reformation began in Germany. Much of its impetus came from the newly founded (in 1540) Jesuit order. It restored Catholicism to many areas, including Bavaria.[17] The Holy Roman Empire became religiously diverse; for the most part, the states of northern and central Germany became Protestant (chiefly Lutheran, but also Calvinist/Reformed) while the states of southern Germany and the Rhineland largely remained Catholic. In 1547 the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V defeated the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Protestant rulers. The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 brought recognition of the Lutheran faith. But the treaty also stipulated that the religion of a state was to be that of its ruler (cuius regio, eius religio).[18]

In 1608/1609 the Protestant Union and the Catholic League formed. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), one of the most destructive conflicts in European history, played out primarily in German lands, but involved most of the countries of Europe. It was to some extent a religious conflict, involving both Protestants and Catholics.[19]

Post-Thirty Years' War period and Protestant church unions (1648–1871)

[edit]

Two main developments reshaped religion in Germany after 1814. There was a movement to unite the larger Lutheran and the smaller Reformed Protestant churches. The churches themselves brought this about in Baden, Nassau, and Bavaria. However, in Prussia King Frederick William III was determined to handle unification entirely on his own terms, without consultation. His goal was to unify the Protestant churches, and to impose a single standardised liturgy, organisation, and even architecture. The long-term goal was to have fully centralised royal control of all the Protestant churches. In a series of proclamations over several decades the Evangelical Church of the Prussian Union was formed, bringing together the more numerous Lutherans and the less numerous Reformed Protestants. The government of Prussia now had full control over church affairs, with the king himself recognised as the leading bishop. Opposition to unification came from the "Old Lutherans" in Prussia and Silesia who followed the theological and liturgical forms they had followed since the days of Luther. The government attempted to crack down on them, so they went underground. Tens of thousands migrated to South Australia and the United States, where they formed the Missouri Synod. Finally, in 1845 the new king, Frederick William IV, offered a general amnesty and allowed the Old Lutherans to form separate free church associations with only nominal government control.[20]: 412–419 [21][22]: 485–491

From the religious point of view of the typical Catholic or Protestant, major changes were underway in terms of a much more personalised religiosity that focused on the individual more than the church or the ceremony. Opposing the rationalism of the late 18th century, there was a new emphasis on the psychology and feeling of the individual, especially in terms of contemplating sinfulness, redemption, and the mysteries and the revelations of Christianity. Pietistic revivals were common among Protestants. Among Catholics there was a sharp increase in popular pilgrimages. In 1844 alone, half a million pilgrims made a pilgrimage to the city of Trier in the Rhineland to view the Seamless robe of Jesus, said to be the robe that Jesus wore on the way to his crucifixion. Catholic bishops in Germany had historically been largely independent of Rome, but now the Vatican exerted increasing control, a new "ultramontanism" of Catholics highly loyal to Rome.[20]: 419–421 A sharp controversy broke out in 1837–38 in the largely Catholic Rhineland over the religious education of children of mixed marriages, where the mother was Catholic and the father Protestant. The government passed laws to require that these children always be raised as Protestants, contrary to Napoleonic law that had previously prevailed and allowed the parents to make the decision. It put the Catholic Archbishop under house arrest. In 1840, the new King Frederick William IV sought reconciliation and ended the controversy by agreeing to most of the Catholic demands. [22]: 498–509

Kulturkampf and the German Empire (1871–1918)

[edit]

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck would not tolerate any base of power outside Germany and launched the Kulturkampf ("culture war") against the power of the pope and the Catholic Church. This gained strong support from German liberals, who saw the Catholic Church as the bastion of reaction and their greatest enemy. The Catholic element, in turn, saw the National Liberals as its worst enemy and formed the Center Party.[23]

Catholics, although about a third of the national population, were seldom allowed to hold major positions in the Imperial government or the Prussian government. After 1871, there was a systematic purge of Catholics; in the powerful interior ministry, which handled all police affairs, the only Catholic was a messenger boy.[24][25]

The German Empire passed the Pulpit Law (1871), which made it a crime for any cleric to discuss political issues, and the Jesuits Law (1872) drove this order out of German territory. In 1873, Bismarck, as prime minister of Prussia, launched further anti-church measures: Public schools and the registration of births, marriages and deaths were transferred from religious authorities (including the Protestant state church) to the state. Germans could now change their religious affiliation through the civil registry. Other German states followed through with similar measures. Nearly all Catholic bishops, clergy, and laymen rejected the legality of the new laws, and were defiant facing the increasingly heavy penalties and imprisonments imposed by Bismarck's government. Historian Anthony Steinhoff reports the casualty totals:

As of 1878, only three of eight Prussian dioceses still had bishops, some 1,125 of 4,600 parishes were vacant, and nearly 1,800 priests ended up in jail or in exile. ...Finally, between 1872 and 1878, numerous Catholic newspapers were confiscated, Catholic associations and assemblies were dissolved, and Catholic civil servants were dismissed merely on the pretence of having Ultramontane sympathies.[26]

The British ambassador Odo Russell reported to London in October 1872 how Bismarck's plans were backfiring by strengthening the ultramontane (pro-papal) position inside German Catholicism:

The German Bishops who were politically powerless in Germany and theologically in opposition to the Pope in Rome – have now become powerful political leaders in Germany and enthusiastic defenders of the now infallible Faith of Rome, united, disciplined, and thirsting for martyrdom, thanks to Bismarck's uncalled for antiliberal declaration of War on the freedom they had hitherto peacefully enjoyed.[27]

Bismarck underestimated the resolve of the Catholic Church and did not foresee the extremes that this struggle would entail.[28][29] The Catholic Church denounced the harsh new laws as anti-catholic and mustered the support of its rank and file voters across Germany. In the following elections, the Center Party won a quarter of the seats in the Imperial Diet.[30] The conflict ended after 1879 for two reasons: Pope Pius IX died in 1878 and was succeeded by the more conciliatory Pope Leo XIII. Bismarck was also looking for greater parliamentary support after his alliance with the National Liberals ended over Bismarck's tariff changes and Social-Democrats emerged as new threat. Following negotiations with Leo XIII,[20]: 568–576 peace was restored: the bishops returned, and the jailed clerics were released. Laws were toned down or taken back (Mitigation Laws 1880–1883 and Peace Laws 1886/87), but the Jesuits Law and the Pulpit Law were not repealed until 1917 and 1953, respectively. The changes concerning schools, civil registry, marriage and religious disaffiliation remain in place today. The Center Party gained strength and became an ally of Bismarck, especially when he attacked socialism.[31]

Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany (1918–1945)

[edit]

The national constitution of 1919 determined that the newly formed Weimar Republic had no state church, and guaranteed freedom of religion. Earlier, these freedoms were mentioned only in state constitutions. Protestants and Catholics were equal before the law, and freethought flourished. The German Freethinkers League attained about 500,000 members, many of whom were atheists, before the organisation was shut down by the Nazis in May 1933.[32]

When Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party seized power in January 1933, it sought to assert state supremacy over all sectors of life. The Reichskonkordat neutralized the Catholic Church as a political force. Through the pro-Nazi Deutsche Christenbewegung ("German Christians movement") and the forced merger of the German Evangelical Church Confederation into the Protestant Reich Church, Protestantism was brought under state control. Following a "gradual worsening of relations" in late 1936, the Nazis supported Kirchenaustrittsbewegung ("movement to leave the church").[33] Although there was no top-down official directive to revoke church membership, some Nazi Party members started doing so voluntarily and put other members under pressure to follow their example.[33] Those who left the churches were designated as Gottgläubig: they believed in a higher power, often a creator-God with a special interest in the German nation, but did not belong to any church, nor were they atheists. Many were Germanic neopagans.[33] This movement, especially promoted by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, remained relatively small and by 1939, 3.5% of Germans identified as Gottgläubig; the overwhelming majority of 94.5% remained Protestant or Catholic, and only 1.5% did not profess any faith.[34] From 1933, Jews in Germany were increasingly marginalised, expelled and persecuted for a combination of religious, racial and economic reasons. From 1941 to the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, they were actively massacred during the Holocaust.[35]

Cold War and contemporary period (1945–present)

[edit]

In the aftermath of World War II, two states emerged in Germany in 1949: West Germany under the aegis of the Western Allies, and East Germany as part of the Soviet bloc. West Germany, officially known as the Federal Republic of Germany, adopted a constitution in 1949 which protected freedom of religion and adopted the regulations of the Weimar Constitution;[37] consequently,[citation needed] secularisation in West Germany proceeded slowly. East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic, had a communist system which actively tried to reduce the influence of religion in society; the government restricted Christian churches and discriminated against Christians.[38][39] In the 21st century, eastern German states, including the area of the former eastern capital, East Berlin, are less religious than western German states.[11]

Religious communities which are of sufficient size and stability and which are loyal to the constitution can be recognised as Körperschaften öffentlichen Rechtes (statutory corporations). This gives them certain privileges – for example, being able to give religious instruction in state schools (as enshrined in the German constitution, though some states are exempt from this) and having membership fees collected (for a fee) by the German revenue department as "church tax" (Kirchensteuer): a surcharge of between 8 and 9% of the income tax. The status mainly applies to the Catholic Church, the mainline Protestant Church in Germany, a number of free churches, and Jewish communities. There has been much discussion about allowing other religious groups (such as Muslims) into this system as well.[39][failed verification]

In 2018 the states of Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg and Bremen made Reformation Day (31 October) a permanent official holiday.[40] This initiative began after the day had been held as a nationwide holiday in 2017, due to the 500th Reformation anniversary of the Reformation, and also due to the fact that the northern German states have significantly fewer holidays than the southern ones.

In 2019 the Catholic News Agency reported that the Catholic church in Germany had a net loss of 216,078 members the previous year. The Protestant churches in Germany had a similar net loss of membership of about 220,000 members. While the total of Catholic and Protestant church membership as of 2019[update] stands at 45 million or 53%, demographers predict that based on current trends it will fall to 23 million by 2060.[41] In 2020 it was reported that the Catholic church in Germany had a 402,000 loss in membership, the largest ever single year decrease up to that point. The Protestant churches in Germany also had a large drop in membership of about 440,000.[42]

Demographics

[edit]

As per the most recent census (May 2022) Catholics are predominant in the south and west, while unaffiliated people are concentrated in the east, where they make up the majority of the population, and are also significant in the north and west of the country, were they make up the majority of the population in metropolitan areas.[43] With the decline of Christianity in the late 20th and early 21st century, accentuated in the east by the official atheism of the former German Democratic Republic, the northeastern states of Germany are now mostly not religious (70%), with many of the people living there being agnostics and atheists.[11]

Immigrations in the late 20th and early 21st century have brought new religions into Germany, including Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Islam. Eastern Orthodoxy is practised among immigrant Greeks, Serbs, Russians, Romanians and other communities.[44] Most Muslims are Sunnis, but there are a small number of Alevis, Shi'a and members of other minority sects.[45] Moreover, Germany has Europe's third-largest Jewish population (after France and the United Kingdom).[46]

Censuses

[edit]In modern Germany, several censuses have been carried out. From the reformation until the 1960s, the majority of the German population was Protestant (mainly Lutherans belonging to the Protestant Church in Germany) while approximatively one-third of the population was Catholic.[47][48] After the German reunification, the religious landscape was significantly changed, as found by the 2011 Census, the first one since the 1960s.

The census in 2011 found that Christianity was the religion of 53,257,550 people or 66.8% of the total population, among whom 24,869,380 or 31.2% were Catholics, 24,552,110 or 30.8% were Protestants of the Protestant Church in Germany, 714,360 or 0.9% were members of Protestant free churches, and 1,050,740 or 1.3% were members of Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. A further 2.6% was affiliated to any other Christian denomination. Jews were 83,430 people or 0.1%, and 4,137,140 or 5.2% were members of other religions. The remaining 22,223,010 people, or 27.9% of the total German population, were not believers in or not members of any religion (including atheists, agnostics and believers in unrecognised religions).[4]

| Religion | 1910[α] | 1925[β] | 1933[β] | 1939[β] | 1946[γ] | 1950[γ] | 1960s[γ][δ] | 1990 | 2001 | 2011[4][52][53] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Christianity | 63,812,000 | 98.3 | 60,208,000 | 96.5 | 62,037,000 | 95.2 | 65,127,000 | 94.0 | 59,973,519 | 94.9 | 65,514,677 | 94.7 | 65,455,144 | 89.4 | 57,947,000 | 73.2 | 52,742,000 | 64.1 | 53,257,550 | 66.8 |

| –EKD and Free Churches | 39,991,000 | 61.6 | 40,015,000 | 64.1 | 40,865,000 | 62.7 | 42,103,000 | 60.8 | 37,240,625 | 59.0 | 40,974,217 | 59.2 | 39,293,907 | 53.7 | 29,422,000 | 37.2 | 26,454,000 | 32.2 | 25,266,470 | 31.7 |

| –Catholicism | 23,821,000 | 36.7 | 20,193,000 | 32.4 | 21,172,000 | 32.5 | 23,024,000 | 33.2 | 22,732,894 | 35.9 | 24,540,460 | 35.5 | 26,161,237 | 35.7 | 28,525,000 | 36.1 | 26,288,000 | 32.0 | 24,869,380 | 31.2 |

| –Eastern Orthodox Christianity | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | – | – | - | 1,050,740 | 1.3 |

| –Other Christians | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2,070,960 | 2.6 |

| Judaism | 615,000 | 1.0 | 564,000 | 0.9 | 500,000 | 0.8 | 222,000 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | – | – | - | 84,430 | 0.1 |

| Other[ε] | 498,000 | 0.7 | 1,639,000 | 2.6 | 2,681,000 | 4.0 | 3,966,000 | 5.7 | 623,956 | 1.0[ζ] | 752,575 | 1.1 | 1,089,673 | 1.5 | – | – | – | - | 4,137,140 | 5.2 |

| No religion | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1,190,629 | 1.5 | 2,572,369 | 4.1[η] | 3,438,020 | 4.9 | 7,459,914 | 10.2 | – | – | – | - | 22,223,010 | 27.9 |

| Total population | 64,926,000 | 100 | 62,411,000 | 100 | 65,218,000 | 100 | 69,314,000 | 100 | 63,169,844 | 100 | 69,187,072 | 100 | 73,178,431 | 100 | 79,112,831 | 100 | 82,259,540 | 100 | 79,652,360 | 100 |

- ^ German Empire borders.

- ^ a b c Weimar Republic borders, i.e. German state borders of 31 December 1937.

- ^ a b c Aggregated data from the Federal Republic of Germany and from the Democratic Republic of Germany, excluding the Saar Protectorate until 1956.

- ^ The censuses were carried out in different years; that of West Germany was done on 6 June 1961 while that of East Germany was done on 31 December 1964.

- ^ Data from 1910 to 1939 included non-religious Germans, non-religious Jews, and people of non-Christian religions, while religious Jews were counted separately. From 1939 onwards non-religious people were counted separately. Data from 1946 to the 1960s included Jews, who otherwise did not have a separate category.

- ^ Excluded members of any non-Christian religion living in East Germany.

- ^ Included members of any non-Christian religion living in East Germany.

Church figures and other estimates

[edit]German major religious bodies publish yearly updated records of their membership.[54]

Only certain religious group publish updated figures on their official membership, and this kind of data is collected in order to levy taxes on the registered membership of those churches, which corresponds to 9% of the total income tax (8% in Baden-Württemberg).[55] According to a study, nearly 29% of the persons who unregistered from their church in 2022 did so in order to avoid paying the church tax.[56] According to a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center, around 20% of people who are not registered to any church nonetheless consider themselves Christians.[57]

According to these church stats, Christianity is the largest religious group in Germany, with around 44.9 million adherents (52.7%) in 2021 of whom 21.6 million are Catholics (26.0%) and 19.7 million are Protestants (23.7%).[5][54]

According to other estimates, Eastern Orthodox Christianity has 1.6 million members or 1.9% of the population.[5][44][54] Other minor Christian religions counted together have approximately 0.8 million members, forming 1.1% of the total population.[5][44][54]

The second largest religion in Germany is Islam, with around 3.0–4.7 million adherents (3.6–5.7% of the population), almost all of whom have full or partial foreign background.[58][5][44] Smaller religious groups include Buddhism (0.2–0.3%), Judaism (0.1%), Hinduism (0.1%), Yazidis (0.1%) and others (0.4%).[5][44] At the end of 2021, 34.9 million or 41.9% of the country's population were not affiliated with any church or religion.[5]

Demographers estimate that in Germany there are around 100,000 religious Jews (Judaism), and a further 90,000 ethnic Jews with no religion, around 100,000 Yazidis, 130,000 Hindus, and 270,000 Buddhists.[44]

Survey data

[edit]| Percentage of the population (right)

Source (left) |

Total

Christianity |

Christian denominations | No religion | Other religions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholicism | Protestants | Eastern Orthodox | Other denominations | Islam | Judaism | Buddhism | Other religions | |||

| Eurobarometer (September 2019)[59] | 61 | 30 | 24 | 2 | 5 | 30 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Eurobarometer (December 2018)[60] | 66.1 | 29.5 | 26.6 | 2.2 | 7.8 | 27.6 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| German General Social Survey (2018)[61] | 63.2 | 29.1 | 31.9 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 33.3 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| International Social Survey Programme (2017)[62] | 63.5 | 30.1 | 31.1 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 33.4 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Politbarometer (2017) entitled to vote only[63] | 66.1 | 32.4 | 33.7 | included in "others" | 29.9 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 1.6 (incl. other Christians) | ||

Religion in Germany 2016 by the German General Social Survey:[61]

- The 2023-2024 European Social Survey found that 23% of Germans identified as Protestant and 22% as Catholic.[64]

- A 2023 IPSOS religion survey found that 24% of Germans identified as Protestant/Evangelical or other christian while 20% identified as Catholic.[65]

- In 2018, according to a study jointly conducted by London's St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society and the Institut Catholique de Paris, and based on data from the European Social Survey 2014–2016, among 16 to 29 years-old Germans 47% were Christians (24% Protestant, 20% Catholic, 2% Eastern Orthodox and 1% other Christian), 7% were Muslims, 1% were of other religions, and 45% were not religious.[66] The data was obtained from two questions, one asking "do you consider yourself as belonging to any particular religion or denomination?" to the full sample of 900 people, and the other one asking "which one?" to the sample who answered "yes".[67]

- In 2017, a survey conducted by Pew Research Center found that 71% of German adult population consider themselves Christians when asking about their current religion (irrespective of whether they are officially members of a particular Christian church). The same survey shows that most of Christians in Germany are non-practicing (defined as people who identify as Christians, but attend church services no more than a few times per year). 5% of people questioned state they have a non-Christian religion and 24% are of no religion.[68]

- In 2016, the German Politbarometer, found that 34.2% of the adult population entitled to vote were Protestants, 31.9% were Catholics, 28.8% were unaffiliated, 2.5% were Muslims, 0.02% were Jews and 1.8% were affiliated with another religion. A further 0.9% did not answer to the question.[69]

- In 2016, the German General Social Survey found that 64.5% of Germans declared themselves to be affiliated to a Christian denomination, 30.5% were Catholics, 29.6% were members of the Evangelical Church, 1.7% were members of the Evangelical Free Church, 1.4% were Eastern Orthodox and 1.3% were other Christians. Non religious people comprised the 32.4% of the population, Muslims were the 2.6% and 0.5% were members of other religions.[70]

- In 2015, Eurobarometer found that 72.6% of the adult population were Christians, the largest Christian denomination being Protestantism, comprising 33.1% of the population, followed by Catholicism with 31.1%, and Eastern Orthodoxy with 0.9%, and unspecified other forms of Christianity with 7.5%. A further 2.2% were Muslims, 0.4% were Buddhists, 0.1% were Jews and 1.3 belonged to other religions. A further 23.5% of the population were not religious, comprising 12.8% who were atheists and 10.7% who were agnostics.[71] The Eurobarometer Poll 2010 found that 44% of German citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", 25% responded that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 27% responded that "they don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force". 4% gave no response.[72]

- According to a 2015 Worldwide Independent Network/Gallup International Association (WIN/GIA) poll,[73] 34% of adult citizens said that they are religious, 42% said that they are not religious and 17% said that they are convinced atheists. 7% gave no response.[74]

Religion by state

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (March 2021) |

In 2016, the survey Politbarometer provided data regarding religion in each of the states of Germany for adults who are entitled to vote (18+), as reported in the table below.[69] Christianity is the dominant religion of Western Germany, excluding Hamburg, which has a non-religious plurality. Northern Germany has traditionally been dominated by Protestantism, especially Lutheranism. The two northernmost provinces of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony have the largest percentage of self-reported Lutherans in Germany.[75] Southern Germany has a Catholic majority, but also a significant Lutheran Protestant population (especially in Northern Württemberg and some parts of Baden and Franconia (Northern Bavaria)), in contrast to the almost entirely Protestant Northern Germany. Irreligion is predominant in Eastern Germany, which was the least religious region amongst 30 countries surveyed in a study in 2012.[76][77][78]

| Religion by state, 2016[69] | Protestants | Catholics | Not religious | Muslims | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37.6% | 40.6% | 16.4% | 2.5% | 3.0% | |

| 23.4% | 58.6% | 15.6% | 1.1% | 1.3% | |

| 24.9% | 3.5% | 69.9% | 0.0% | 1.5% | |

| 51.8% | 7.8% | 39.1% | 0.0% | 1.3% | |

| 14.3% | 7.5% | 74.3% | 1.5% | 2.4% | |

| 32.0% | 12.4% | 43.5% | 8.5% | 3.5% | |

| 34.3% | 9.0% | 44.1% | 10.9% | 1.7% | |

| 50.2% | 21.7% | 22.2% | 3.8% | 2.1% | |

| 53.8% | 18.7% | 24.1% | 2.5% | 0.9% | |

| 24.9% | 3.9% | 70.0% | 0.3% | 0.9% | |

| 30.9% | 44.6% | 18.1% | 4.4% | 2.0% | |

| 34.8% | 42.4% | 19.6% | 1.0% | 2.1% | |

| 22.3% | 68.1% | 8.2% | 1.4% | 0.0% | |

| 27.6% | 4.0% | 66.9% | 0.3% | 1.1% | |

| 18.8% | 5.1% | 74.7% | 0.3% | 1.2% | |

| 61.5% | 3.2% | 31.3% | 2.2% | 1.7% | |

| 27.8% | 9.5% | 61.2% | 0.0% | 1.5% | |

| 34.5% | 32.2% | 29.0% | 2.5% | 1.8% |

Personal beliefs

[edit]According to a survey by Pew Research Center in 2017, 60% of German adult population believe in God, while 36% do not believe in God (9% don't believe in God but in a higher power, 27% do not believe in God or any higher power):[79]

| Belief | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Believe in God (Monotheism) | 60 | |

| Believe in God, absolutely certain | 10 | |

| Believe in God, fairly certain | 37 | |

| Believe in God, not too certain | 12 | |

| Believe in God, not at all certain | 1 | |

| Believe in a higher power or spiritual force (Ietsism) | 9 | |

| Do not believe in God or any higher power or spiritual force (Atheism) | 27 | |

| Don't know (Agnosticism) or refused to answer | 4 | |

Christianity

[edit]At its foundation in 1871, about two-thirds of the population of the German Empire belonged to a state Protestant church;[a] in 2021 the Protestant Church in Germany was the faith of 23.7%. In 1871, one-third of the population was Catholic; in 2021 its membership was 26.0%. Other faiths have existed in the state, but never achieved the demographic significance and cultural impact of these denominations.

As of 2021, Christianity, with around 44.9 million members, was the largest religion in Germany (52.7% of the population) [5][44][54] Consequently, a majority of the German people belong to a Christian community, although many of them take no active part in church life. About 1.9% of the population was Eastern Orthodox Christian in 2021, and about 1.1% followed other forms of Christianity (including other Protestant churches, Jehovah's Witnesses, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and others).[5][44][54]

Protestantism

[edit]

- Protestant Church in Germany — 18,560,000 (2023) — 21.9% of the German population[80]

- Free Baptist and Mennonite Groups — 290,000 (2007)

- Baptists (mostly Union of Evangelical Free Churches in Germany; see Baptists in Germany) — 80,195 (2020)[81]

- Methodists — 52,031 (2016)

- Pentecostals (Bund Freikirchlicher Pfingstgemeinden) — 51,896 (2015)

- Mennonites — 51,771 (2022)[82]

- Bund Freier evangelischer Gemeinden — 41,203 (2017)

- Seventh-day Adventist Church — 34,811 (2014)

- Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church — 33,175 (2014)

- Independent African Churches — 30,000 (2005)

- Evangelical Lutheran Free Church — 1,300 (2017)[83]

Catholicism

[edit]Catholic churches in full communion:

- Roman Catholic Church in Germany — 20,346,000 (2023) — 24% of the German population[80]

- Maronite Church Catholics — 6,000[44]

Church not in communion:

- Old Catholic Church — 15,715[44]

Eastern Christianity

[edit]

- Orthodox Christians — around 1.6 million (1.9%)[84]

- Eastern Orthodox Churches

- Churches of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople — 570,000[84]

- Greek Orthodox Church — 410,000[84]

- Ukrainian Orthodox Eparchy of Western Europe — 10,000[84]

- Patriarchal Exarchate for Orthodox Parishes of the Russian Tradition in Western Europe — 200[84]

- Serbian Orthodox Church — 337,000[84]

- Russian Orthodox Church — 270,000[84]

- Romanian Orthodox Church — 150,000[84]

- Ukrainian Orthodox — 143,000[84]

- Bulgarian Orthodox Church — 130,000[84]

- Churches of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople — 570,000[84]

- Oriental Orthodox Churches

- Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch — 100,000[84]

- Armenian Apostolic Church — 35,000[84]

- Coptic Orthodox Church — 22,000[84]

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church — 20,000[84]

- Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church — 15,000[84]

- Eastern Orthodox Churches

- Church of the East

- Assyrian Church of the East — 10,000[84]

Others

[edit]- New Apostolic Church — 341,202 (2015)

- Jehovah's Witnesses — 168,763[44]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — 38,739[44]

- The Christian Community — 20,000 (2010)

No religion

[edit]As of 2021, 34.9 million or 41.9% of the Germans are irreligious.[85][5][44] Before World War II, about two-thirds of the German population was Protestant and one-third was Roman Catholic. In the north and northeast of Germany especially, Protestants dominated.[86] In the former West Germany between 1945 and 1990, which contained nearly all of Germany's historically Catholic areas, Catholics have had a small majority since the 1980s. Due to a generation behind the Iron Curtain, Protestant areas of the former states of Prussia were much more affected by secularism than predominantly Catholic areas. The predominantly secularised states, such as Hamburg or the East German states, used to be Lutheran or United Protestant strongholds. Because of this, Protestantism is now strongest in two strips of territory in the former West Germany, one extending from the Danish border to Hesse, and the other extending northeast–southwest across southern Germany.

There is a non-religious majority in Hamburg, Bremen, Berlin, Brandenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. In the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt, only 19.7% belong to the two main denominations of the country.[87] This is the state where Martin Luther was born and lived most of his life.

In what used to be East Germany both religious observance and affiliation are much lower than in the rest of the country, after forty years of Communist rule. The government of the German Democratic Republic encouraged a state atheist worldview through institutions such as Jugendweihen (youth consecrations) — secular coming-of-age ceremonies akin to Christian confirmation which all young people were encouraged to attend. The number of christenings, religious weddings, and funerals is also lower than in the West.

According to a survey among German youths (aged 12 to 24) in the year 2006, most German youths are non-religious (51%). 30% of German youths stated belief in a personal god, 19% believe in some kind of supernatural power, 23% share agnostic views and 28% are atheists.[88]

Islam

[edit]

Islam is the largest non-Christian religion in the country. There are between 3.0 and 4.7 million Muslims, around 3.6% of the population.[5][89] The majority of Muslims in Germany are of Turkish origin, followed by those from Pakistan, countries of the former Yugoslavia, Arab countries, Iran, and Afghanistan. This figure includes the different denominations of Islam, such as Sunni, Shia, Ahmadi, and Alevi. Muslims first came to Germany as part of the diplomatic, military, and economic relations between Germany and the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century.[90]

Between 2010 and 2016, the number of Muslims living in Germany increased from 3.3 million (4.1% of the population) to nearly 5 million (6.1%). The most important factor in the growth of Germany's Muslim population is immigration.[91]

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhists are the third largest group of believers in Germany after different religious denominations of Christianity and Islam. There are around 270,000 Buddhists who are living in Germany.[44]

Most of them are followers of the Buddhist school of Theravada especially from Sri Lanka. Furthermore, there are followers of Vajrayana, also referred to as Tibetan Buddhism as well as followers of Nichiren Buddhism mainly from Japan and Zen Buddhism from Japan, as well. Around 59,000 Buddhists are from Thailand who follow the school of Theravada and keep 48 temples in Germany and form one of the largest Buddhist community of Buddhists of Asian origin in Germany. A large portion of Buddhists in Eastern Germany are part of the Vietnamese community. Most of the different Buddhist schools and organisation in Germany are members of the non-profit association Deutsche Buddhistische Union e.V. (DBU).

Judaism

[edit]

Jewish communities in German speaking regions go back to the fourth century.[93] In 1910, about 600,000 Jews lived in Germany. After Adolf Hitler assumed power in 1933, he began systematically persecuting Jews in Germany. Systematic mass murder of Jews in German-occupied Europe began with the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. By the end of World War II, four years later, around 6 million Jews had been killed by the National Socialist government.[94]

About ninety thousand Jews from the former Eastern Bloc, mostly from ex-Soviet Union countries, have settled in Germany since the fall of the Berlin Wall. This is mainly due to a German government policy which effectively grants an immigration opportunity to anyone from the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Baltic states with Jewish heritage, and the fact that today's Germans are seen as more significantly accepting of Jews than many people in ex-Soviet regions.

Recently, antisemitic abuse against Jews in Germany has increased. The Central Council of Jews has urged Jewish Germans to avoid wearing their kippahs in public.[95]

- Total religious Jews — 100,000 (0.1%)[5][44]

- Jews whose religious status is not ascertained — 90,000.[44] They come from Eastern Europe and have no membership in any Jewish community.[44]

- Union of Progressive Jews in Germany — 5,000 members[44]

- Central Council of Jews in Germany — 23 national associations of 108 communities comprising approximately 100,500 members in 2014.[96]

Hinduism

[edit]

There are approximately 100,000 Hindus living in Germany.[44] Most of them are Tamil Hindus from Sri Lanka (around 42,000 to 45,000); from India are around 35,000 to 40,000; of German or European origin are around 7,500 and around 5,000 Hindus are originally from Afghanistan. There are also Hindus from Nepal in Germany however this number is very low.

In addition, there are Hindus in Germany who are followers of New religious movements such as Hare Krishna movement, Bhakti yoga, and Transcendental Meditation. However, the total number of these followers in Germany is comparatively low.

Other religions

[edit]Yazidism

[edit]There is a large Yazidi community in Germany, estimated to be numbering around 100,000 people.[44] This makes the German Yazidi community one of the largest Yazidi communities in the Yazidi diaspora.

Sikhism

[edit]Between 10,000 and 20,000 Sikhs are living in Germany.[44] Many Sikhs in Germany have their roots from Punjab region in the north of India, as well as from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Germany has the third highest Sikh population in Europe after United Kingdom and Italy. The city Frankfurt is also known to the Sikhs, as Mini Punjab, because of a great Sikh Population, residing there.

Druze Faith

[edit]In 2020, there were more than 10,000 Druze living in Germany, with the largest concentration in Berlin and North Rhine-Westphalia.[97] The number of Druze has increased in recent years with thousands of Syrian refugees of the Syrian Civil War entered Germany to seek refugee status.[98] Druze in Germany are mostly of Syrian descent, and they practice Druzism, a monotheistic religion encompasses aspects of Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, Judaism and Greek philosophy, among influences.[99]

Baháʼí Faith

[edit]

A 1997–8 estimate is of 4000 Bahá'ís in Germany. In 2002 there were 106 Local Spiritual Assemblies. The 2007-8 German Census using sampling estimated 5–6,000 Bahá'ís in Germany. The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 11,743 Bahá'ís.Following the German reunification in 1989–91 the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany handed down a judgment affirming the status of the Bahá'í Faith as a religion in Germany. Continued development of youth oriented programs included the Diversity Dance Theater (see Oscar DeGruy) which traveled to Albania in February 1997. Udo Schaefer et al.'s 2001 Making the Crooked Straight was written to refute a polemic supported by the Protestant Church in Germany written in 1981. Since its publication the Protestant Church in Germany has revised its own relationship to the German Bahá'í Community. Former member of the federal parliament Ernst Ulrich von Weizsaecker commended the ideas of the German Bahá'í community on social integration, which were published in a statement in 1998, and Chancellor Helmut Kohl sent a congratulatory message to the 1992 ceremony marking the 100th Anniversary of the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh.

Neopaganism

[edit]

Neopagan religions have been public in Germany at least since the 19th century. Nowadays Germanic Heathenism (Germanisches Heidentum, or Deutschglaube for its peculiar German forms) has many organisations in the country, including the Germanische Glaubens-Gemeinschaft (Communion of Germanic Faith), the Heidnische Gemeinschaft (Heathen Communion), the Verein für germanisches Heidentum (Association for Germanic Heathenry), the Nornirs Ætt, the Eldaring, the Artgemeinschaft, the Armanen-Orden, and Thuringian Firne Sitte.

Other Pagan religions include the Celto-Germanic Matronenkult grassroots worship practiced in Rhineland, Celtoi (a Celtic religious association), and Wiccan groups. As of 2006, 1% of the population of North Rhine-Westphalia adheres to new religions or esoteric groups.

Sekten and new religious movements

[edit]

The German government provides information and warnings about cults, sects, and new religious movements. In 1997, the parliament set up a commission for Sogenannte Sekten und Psychogruppen (literally "so-called sects and psychic groups"), which in 1998 delivered an extensive report on the situation in Germany regarding NRMs.[100] In 2002, the Federal Constitutional Court upheld the governmental right to provide critical information on religious organisations being referred to as Sekte, but stated that "defamatory, discriminating, or falsifying accounts" were illegal.[101]

When classifying religious groups, the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD) use a three-level hierarchy of "churches", "free churches" and Sekten:

- Kirchen (churches) is the term generally applied to the Roman Catholic Church, the Protestant Church in Germany's member churches (Landeskirchen), and the Orthodox Churches. The churches are not only granted the status of a non-profit organisation, but they have additional rights as statutory corporations (German: Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts), which means they have the right to employ civil servants (Beamter), do official duties, or issue official documents.

- Freikirchen (free churches) is the term generally applied to Protestant organisations outside of the EKD, e.g. Baptists, Methodists, independent Lutherans, Pentecostals, Seventh-day Adventists and others. However, the Old Catholics can be referred to as a free church as well.[102] The free churches are not only granted the tax-free status of a non-profit organisation, but many of them have additional rights as statutory corporations.

- Sekten is the term for religious groups which do not see themselves as part of a major religion (but perhaps as the only real believers of a major religion).[103]

Every Protestant Landeskirche (church whose canonical jurisdiction extends over one or several states, or Länder) and Catholic episcopacy has a Sektenbeauftragter (Sekten delegate) from whom information about religious movements may be obtained.

Freedom of religion

[edit]In 2023, Freedom House scored Germany 4 out of 4 for religious freedom.[104]

See also

[edit]- Religion by country

- Heathenry (new religious movement)

- History of Germany

- Roman Catholicism (especially the Catholic Church in Germany)

- Protestantism (especially Protestantism in Germany and the Protestant Church in Germany)

- Lutheranism

- Calvinism

- United and uniting churches (especially the Prussian Union of churches)

- Landeskirche and Freikirche

- Anabaptism

- Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation

- Max Weber (the Protestant work ethic)

- State atheism in the former East Germany

Notes

[edit]- ^ German Protestantism has been overwhelmingly a mixture of Lutheran, Reformed (i.e. Calvinist), and United (Lutheran & Reformed/Calvinist) churches, with Baptists, Pentecostals, Methodists, and various other Protestants being only a recent development.

References

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Germany |

|---|

|

| Festivals |

| Music |

- ^ a b c "Religionszugehörigkeiten 2023" [Religious denominations 2023]. fowid.de (in German). fowid ('Worldviews in Germany Research Group'). 28 August 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ a b Robert Kolb, Confessing the faith: reformers define the Church, 1530–1580 (Concordia Publishing House, 1991)

- ^ a b "Kirchenmitglieder 1953-2023" [Membership of churches 1953-2023]. fowid.de (in German). Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland (fowid). 4 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Zensusdatenbank – Ergebnisse des Zensus 2011 –Personen nach Religion (ausführlich) für Deutschland". Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Religionszugehörigkeiten 2021". 24 August 2022.

- ^ "BAMF-Forschungszentrum: Neue Studie Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland 2020 zeigt mehr Vielfalt" (in German). Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland 2020" (in German). Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues", Pew Research Center, October 29, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ "Europeans and Biotechnology in 2010", Eurobarometer, European Commission, November 2010

- ^ "Values and identities of EU citizens", Eurobarometer, European Commission, November 2021

- ^ a b c Goddyn, Sophie L. (29 April 2014). The Most Godless Region of the World: Atheism in East Germany. Young Historians Conference. Portland State University. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016.

- ^ "Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism" (PDF). Gallup. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2017.

- ^ Leerssen, Joep Leerssen (Spring 2016). "Gods, Heroes, and Mythologists: Romantic Scholars and the Pagan Roots of Europe's Nations" (PDF). History of Humanities. 1 (1): 71–100. doi:10.1086/685061. hdl:11245.1/5020749c-8808-435e-9251-137e66636e33. S2CID 191884337.

- ^ Pohlsander, Hans A. (4 Sep 2012) [20 July 2003]. "Constantine I (306 – 337 A.D.)" Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Accessed 15 May 2018.

- ^ Regents of the University of Michigan. "Historic Illustrations of Art and Architecture". University of Michigan Library. Accessed 15 May 2018.

- ^ John Lotherington, The German Reformation (2014)

- ^ Marvin R. O'Connell, Counter-reformation, 1559–1610 (1974)

- ^ Lewis W. Spitz, "Particularism and Peace Augsburg: 1555," Church History (1956) 25#2 pp. 110–126 in JSTOR

- ^ Compare:

Wilson, Peter Hamish (2009). The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780674036345. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

[...] it was not primarily a religious war. [...] Religion certainly provided a powerful focus for identity, but it had to compete with political, social, linguistic, gender and other distinctions. most contemporary observers spoke of imperial, Bavarian, Swedish, or Bohemian troops, not Catholic or Protestant, which are anachronistic labels used for convenience since the nineteenth century to simplify accounts. The war was religious only to the extent that faith guided all early modern public policy and private behaviour.

- ^ a b c Clark, Christopher M. (2006). Iron Kingdom: The rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, Mass. (US): Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02385-7.

- ^ Christopher Clark, "Confessional policy and the limits of state action: Frederick William III and the Prussian Church Union 1817–40." Historical Journal 39.04 (1996) pp. 985–1004. in JSTOR

- ^ a b Holborn, Hajo (1964). "Schools and Churches in the Early Nineteenth Century". A History of Modern Germany. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 472–509.

- ^ Douglas W. Hatfield, "Kulturkampf: The Relationship of Church and State and the Failure of German Political Reform," Journal of Church and State (1981) 23#3 pp. 465–484 in JSTOR(1998)

- ^ John C.G. Roehl, "Higher civil servants in Germany, 1890–1900" in James J. Sheehan, ed., Imperial Germany (1976) pp. 128–151

- ^ Margaret Lavinia Anderson, and Kenneth Barkin. "The myth of the Puttkamer purge and the reality of the Kulturkampf: Some reflections on the historiography of Imperial Germany." Journal of Modern History (1982): 647–686. esp. pp. 657–662 in JSTOR

- ^ Anthony J. Steinhoff, "Christianity and the creation of Germany," in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley, eds., Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8: 1814–1914 (2008) p. 295

- ^ Quoted in Edward Crankshaw, Bismarck (1981) pp. 308–309

- ^ John K. Zeender in The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 3 (Oct., 1957), pp. 328–330.

- ^ Rebecca Ayako Bennette, Fighting for the Soul of Germany: The Catholic Struggle for Inclusion after Unification (Harvard U.P. 2012)

- ^ Blackbourn, David (December 1975). "The Political Alignment of the Centre Party in Wilhelmine Germany: A Study of the Party's Emergence in Nineteenth-Century Württemberg" (PDF). Historical Journal. 18 (4): 821–850. doi:10.1017/s0018246x00008906. JSTOR 2638516. S2CID 39447688.

- ^ Ronald J. Ross, The failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf: Catholicism and state power in imperial Germany, 1871–1887 (1998).

- ^ "Atheist Hall Converted: Berlin Churches Establish Bureau to Win Back Worshipers". The New York Times. 14 May 1933. p. 2. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Steigmann-Gall, Richard (2003). The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 9780521823715. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Ziegler, Herbert F. (2014). Nazi Germany's New Aristocracy: The SS Leadership, 1925–1939. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 85–87. ISBN 9781400860364. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "antisemitisme §2. Oorzaken"; "holocaust". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ "Gottesdienstschilder jetzt für alle Religionsgemeinschaften" [Worship signs now for all religious communities] (in German). Apd.info. 20 October 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Basic Law Art. 140

- ^

Allinson, Mark (2000). "The churches' basis challenged". Politics and Popular Opinion in East Germany, 1945–68. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780719055546. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

[...] the SED's basic outlook towards the churches remained constant, even though the New Course had forced a premature end to the first phase of the party's efforts to restrict religious influence over youth.

- ^ a b "Resources on Faith, Ethics, and Public Life: Germany". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013.

The Basic Law of Germany guarantees religious freedom and lays out the general structure of church-state relations. Religious communities may organize into 'statutory corporations' in order to receive tax privileges and give religious instruction in public schools. There is a growing Muslim community as a result of decades of immigration, mainly from Turkey, which still lacks full state recognition.

- ^ SPIEGEL, DER (February 2018). "Reformationstag: Norddeutschland soll einen neuen Feiertag bekommen - DER SPIEGEL - Job & Karriere". Der Spiegel.

- ^ "Catholic Church in Germany lost 200,000 members last year". CNA News. Catholic News Agency. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

According to the German Bishops' Conference, the Catholic Church in the country declined by 216,078 members last year. Protestant churches saw a similar drop, with 220,000 members leaving during that time period. [...] Some 53% of the country's population remains either Catholic or Protestant, according to DW. Both churches currently have more than 20 million members. [...] However, the University of Freiburg predicted that membership in both churches will be cut in half by 2060, dropping from a combined total of 45 million currently to below 23 million in the next 40 years.

- ^ "Catholic Church in Germany lost a record number of members last year". CNA News. Catholic News Agency. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Ergebnisse des Zensus 2022: Religionszugehörigkeit (in German), Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder, 2 July 2024. (Spreadsheet file direct download: 83kB)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "REMID — Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst" (in German). 2017.

- ^ Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland [Muslim Life in Germany] (in German). Nuremberg: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (German: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge), an agency of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Germany). June 2009. pp. 97–80. ISBN 9783981211511. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Blake, Mariah (10 November 2006). "In Nazi cradle, Germany marks Jewish renaissance". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ a b "Bevölkerung nach Religionszugehörigkeit (1910–1939)" (PDF). Band 6. Die Weimarer Republik 1918/19–1933. Deutsche Geschichte in Dokumenten und Bildern (in German). Washington, DC: Deutschen Historischen Instituts.

- ^ a b "Deutschland: Die Konfessionen" (in German). FOWID. 15 January 2018.

- ^ Bischofskonferenz, Deutsche. "Kirchliche Statistik". dbk.de (in German). Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ "Zahlen und Daten zu Kirchenmitgliedern". www.ekd.de (in German). Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ "Population change – Demographic balance and crude rates at national level". Eurostat. 1960–2019.

- ^ "Pressekonferenz "Zensus 2011 – Fakten zur Bevölkerung in Deutschland"" (PDF). DESTATIS. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "ZENSUS2011 – Übersicht Fragebogen". www.zensus2011.de. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Numbers and Facts about Church Life in the EKD 2021 Report. Evangelical Church of Germany. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ James (5 November 2017). "What Is German Church Tax And How Do I Avoid Paying It?". Live Work Germany. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Umfrageergebnis". Kirchenaustritt.de (in German). Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ "A Look at Church Taxes in Western Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Study of BAMF 14. December 2016" (PDF).

- ^ "Special Eurobarometer 493". European Union: European Commission: 229–230. September 2019.

- ^ Eurobarometer 90.4: Attitudes of Europeans towards Biodiversity, Awareness and Perceptions of EU customs, and Perceptions of Antisemitism. European Commission. Retrieved 9 August 2019 – via GESIS.

- ^ a b "Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2018". zacat.gesis.org. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "International Social Survey Programme: Social Networks and Social Resources – ISSP 2017". zacat.gesis.org. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Politbarometer 2017 (Kumulierter Datensatz)". zacat.gesis.org. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7c0cc073-40cd-4b11-b83e-09b3a5583a65_2700x2400.png. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Global Religion 2023 - Religious Beliefs Across the World, Ipsos, Paris.

- ^ Bullivant, Stephen (2018). "Europe's Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014–16) to inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops" (PDF). St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society; Institut Catholique de Paris. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2018.

- ^ "European Social Survey, Online Analysis". nesstar.ess.nsd.uib.no. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Being Christian in Western Europe (survey among 24,599 adults (age 18+) across 15 countries in Western Europe)". Pew Research Center. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Konfession, Bundesland – weighted (Kumulierter Datensatz)". Politbarometer 2016. Question V312. 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2017 – via GESIS. Description of study's sample.

- ^ "Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2016". GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences (in German). 2016. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ European Commission (2015). Special Eurobarometer 84.3, Discrimination in the EU in 2015, Question sd3.F1, via GESIS

- ^ Eurobarometer Biotechnology report 2010 p. 381

- ^ "Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism – 2012" (PDF). RED C Research & Marketing Ltd. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Losing our religion? Two thirds of people still claim to be religious" (PDF). WIN Gallup International. 13 April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2015.

- ^ Evangelische Kirche Deutschlands. "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen am 31.12.2010" (PDF). EDK. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Belief about God across Time and Countries, Tom W. Smith, University of Chicago, 2012" (PDF).

- ^ "Why Eastern Germany is the Most Godless Place on Earth". Die Welt. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012.

- ^ "East Germany the "most atheistic" of any region". Dialog International. 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Being Christian in Western Europe Topline (survey among 24,599 adults (age 18+) across 15 countries in Western Europe)" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Religionszugehörigkeiten 2023". Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland (fowid.de) (in German). 28 August 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Union of Evangelical Free Churches (Baptists) in Germany". Baptist World Alliance. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ "MWC World Map 2022" (PDF). MWC-CMM. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Evangelical Lutheran Free Church—Germany". celc.info.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "REMID — Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst – Mitgliederzahlen: Orthodoxe, Orientalische und Unierte Kirchen" (in German). 2017.

- ^ "Kirchenmitglieder: 49,7 Prozent". fowid (in German). 27 June 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Ericksen, Robert P.; Heschel, Susannah (1999). Betrayal: German Churches and the Holocaust. Minneapolis (US): Fortress Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8006-2931-1.

- ^ "Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland: Kirchenmitgliederzahlen am 31.12.2004" [Protestant Church in Germany: Membership on 31.12.2004] (PDF) (in German). Protestant Church in Germany. December 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Thomas Gensicke: Jugend und Religiosität. In: Deutsche Shell Jugend 2006. Die 15. Shell Jugendstudie. Frankfurt a.M. 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "REMID — Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst – Mitgliederzahlen: Islam" (in German). 2017.

- ^ Anwar, Muhammad; Blaschke, Jochen; Sander, Åke (2004). "Islam and Muslims in Germany: Muslims in German History until 1945" (PDF). State Policies Towards Muslim Minorities: Sweden, Great Britain and Germany. editionParabolis. pp. 65–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2004.

- ^ Mitchell, Travis (29 November 2017). "The Growth of Germany's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project.

- ^ Der Tagesspiegel: Moschee in Wilmersdorf: Mit Kuppel komplett, 29 August 2001, Retrieved 27 January 2016

- ^ "Germany: Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Documenting Numbers of Victims of the Holocaust and Nazi Persecution". encyclopedia.ushmm.org.

- ^ "Germany's Jews urged not to wear kippahs after attacks". BBC News. 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Zentralrat – Mitglieder" [Central Council – Members]. Central Council of Jews in Germany (in German). Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Drusentum - Die geheime Religion (2020)". Deutschlandfunk. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Drusentum - Die geheime Religion (2020)". Deutschlandfunk. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Dating Druze: The struggle to find love in a dwindling diaspora". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Final Report of the Enquete Commission on 'So-called Sects and Psychogroups': New Religious and Idealogical Communities and Psychogroups in the Federal Reputblic of Germany (PDF). Bonner Universitäts-Buchdruckerei. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2005.

- ^ Decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court: BVerfG, Urteil v. 26.06.2002, Az. 1 BvR 670/91

- ^ "Freikirche: Altkatholische Kirche" [Free Church: Old Catholic Church]. uni-protokolle.de. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ "Sekten: Definitionen" [Sects: Definitions] (in German). hilfe24.de. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ "Germany: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report". Freedom House. 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Büttner, Manfred (1980). "On the history and philosophy of the geography of religion in Germany." Religion 10 (1): 86–119.

- Drummond, Andrew Landale (1951). German Protestantism since Luther.

- Eberle, Edward J. (2003). "Free Exercise of Religion in Germany and the United States." Tulane Law Review 78 (2003): 1023 onwards.

- Elon, Amos (2002). The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany, 1743–1933.

- Evans, Ellen Lovell (1981). The German Center Party, 1870–1933: A Study in Political Catholicism. Southern Illinois UP

- Evans, Richard J. (1982). "Religion and society in modern Germany". European History Quarterly 12 (3): 249–288.

- Fetzer, Joel S.; Soper, J. Christopher (2005). Muslims and the state in Britain, France, and Germany. Cambridge University Press. (Excerpt).

- Gay, Ruth (1992). The Jews of Germany: A Historical Portrait.

- Harrington, Joel F.; Smith, Helmut Walser (1997). "Confessionalization, community, and state building in Germany, 1555–1870". Journal of Modern History (1997): 77–101. online; JSTOR.

- Kastoryano, Riva (2004). "Religion and incorporation: Islam in France and Germany". International Migration Review 38 (3): 1234–1255.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, I: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: Background and the Roman Catholic Phase (1959); Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, II: The Nineteenth Century in Europe: The Protestant and Eastern Churches (1959); Christianity in a Revolutionary Age, IV: The Twentieth Century in Europe: The Roman Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Churches (1959) – multiple chapters on Germany.

- Roper, Lyndal; Scribner, Robert W. (2001). Religion and Culture in Germany: (1400–1800). Brill. (Online).

- Scribner, Robert W.; Dixon, C. Scott (2003).German Reformation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, Helmut Walser, ed. (2001). Protestants, Catholics and Jews in Germany, 1800–1914. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Spohn, Willfried (1991). "Religion and Working-Class Formation in Imperial Germany 1871–1914". Politics & Society 19 (1): 109–132.

- Tal, Uriel (1975). Christians and Jews in Germany: Religion, politics, and ideology in the Second Reich, 1870–1914. Cornell University Press

- Thériault, Barbara (2004). 'Conservative Revolutionaries': Protestant and Catholic Churches in Germany after Radical Political Change in the 1990s – focus on merger of GDR after 1990.