Escape from Alcatraz (film)

| Escape from Alcatraz | |

|---|---|

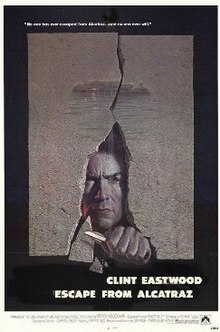

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Don Siegel |

| Screenplay by | Richard Tuggle |

| Based on | Escape from Alcatraz by J. Campbell Bruce |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Jerry Fielding |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8 million[1] |

| Box office | $43 million[2] |

Escape from Alcatraz is a 1979 American prison thriller film[3][4][5] directed and produced by Don Siegel. The screenplay, written by Richard Tuggle, is based on the 1963 non-fiction book of the same name by J. Campbell Bruce, which recounts the 1962 prisoner escape from the maximum security prison on Alcatraz Island. The film stars Clint Eastwood as escape ringleader Frank Morris, alongside Patrick McGoohan, Fred Ward, Jack Thibeau, and Larry Hankin with Danny Glover appearing in his film debut.[6]

The film marks the fifth and final collaboration between Siegel and Eastwood, following Coogan's Bluff (1968), Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970), The Beguiled (1971), and Dirty Harry (1971).

Released by Paramount Pictures on June 22, 1979, Escape from Alcatraz received critical acclaim and was a financial success, one of the highest-grossing films of 1979.[7][2]

Plot

[edit]In early 1960, Frank Morris, a career criminal notorious for having escaped from several previous facilities, arrives at the maximum security prison on Alcatraz Island. Alcatraz is unique within the US prison system for its high level of security; no inmate has ever escaped. The day of his arrival, Morris steals a nail clipper from the Warden's desk during the intake process.

Over the next days, Morris makes acquaintances with his fellow inmates: the eccentric Litmus, who is fond of desserts; English, a black inmate serving two life sentences for killing two white men in self-defense; and the elderly Doc, who paints portraits and once grew chrysanthemums at Alcatraz. Doc's portraits contain chrysanthemums as a symbol of human spirit and freedom. He makes a gift of one of the blossom heads to Morris. Morris also makes an enemy of Wolf, a rapist who harasses him in the showers and later attacks him in the prison yard with a knife; both men are subsequently imprisoned in isolation in the hole.

Morris is later released while Wolf is kept locked up. The Warden discovers that Doc has painted a portrait of him, as well as other guards. The guards' paintings are flattering, recognizing their humanity, but the Warden's painting, which has been kept out of view, captures what Doc sees as the ugliness of his cruel nature. Enraged, the Warden burns the painting and strips Doc of his privileges. Doc falls into depression and while sitting in the prison workshop cuts off several fingers with a hatchet before the guards stop him.

Later, Morris encounters bank-robbing brothers John and Clarence Anglin, who are his old friends from another prison sentence, and forms a partnership with inmate Charley Butts. Morris notices that the concrete around the grille in his cell is weak and can be chipped away, which evolves into an escape plan. Over the next months, Morris, the Anglins, and Butts dig through the walls of their cells with spoons (having soldered them with heat to form makeshift shovels), fashion dummies out of paper-mâché and human hair to plant in their beds and construct a primitive raft from raincoats. During mealtime, Morris places a chrysanthemum at the table in honor of Doc, but the Warden stops by and crushes it, causing a provoked Litmus to suffer a heart attack. After a search of Morris' cell turns up nothing during a routine contraband search, the Warden orders him to be transferred to a more secure wing of Alcatraz. Wolf is released from solitary confinement and prepares to attack Morris again, but English manages to intercept him by threatening Wolf with his own gang.

That night, the inmates decide they are now ready to leave. Morris, the Anglins and Butts plan to meet in the passageway and escape. Butts loses his nerve and fails to rendezvous with them. He later changes his mind but is too late and returns to his cell to sulk over his missed opportunity. Carrying the flotation gear, Morris and the Anglins access the roof and avoid the searchlights. They scramble down the side of the building into the prison yard, climb over a barbed-wire fence, make their way to the shoreline of the island and inflate the raft. The men depart from Alcatraz, partially submerged in the water, clinging to the raft and using their legs to propel themselves.

The following morning, the escape is discovered, and a manhunt ensues. Shreds of raincoat material and personal effects of the men are found floating in the bay. While searching on Angel Island, the humiliated Warden insists that the men's personal effects were important, and the men would have drowned before leaving them behind. A guard notes the possibility that the men simply threw them in so it would look like they drowned. The Warden is later summoned to go to Washington and face his superiors, with the prospect of being forced to accept an early retirement/termination of his duties for having failed to prevent the breakout from happening. On a rock, he finds a chrysanthemum flower head and is told by his aide that none grow on Angel Island.

A post-script states that the fugitives are never found and Alcatraz as a prison closed less than a year later.

Cast

[edit]- Clint Eastwood as Frank Morris

- Patrick McGoohan as the Warden

- Fred Ward as John Anglin

- Jack Thibeau as Clarence Anglin

- Larry Hankin as Charley Butts

- Roberts Blossom as Chester "Doc" Dalton

- Paul Benjamin as English

- Bruce M. Fischer as Wolf

- Frank Ronzio as Litmus

- Fred Stuthman as Johnson

- David Cryer as Wagner

- Danny Glover and Carl Lumbly as inmates

Historical accuracy

[edit]The film's final scene implies that the escape was successful, but in fact it remains a mystery whether this is so.[8] Circumstantial evidence uncovered in the early 2010s seemed to suggest that the men had survived, and that, contrary to the official FBI report of the escapees' raft never being recovered and no car thefts being reported, a raft was discovered on nearby Angel Island with footprints leading away (similar to the fictional scene in the movie where the Warden finds a chrysanthemum possibly left by the escapees).[9][8][10]

The character Charley Butts was based on a fourth inmate, Allen West, who did participate in the real escape but was left behind when he couldn't remove his ventilator grille on the night of the escape. He aided the FBI's official investigation of the escape.

The Warden as portrayed in the film is a fictional character. The film is set between the arrival of Morris at Alcatraz in January 1960 and his escape in June 1962. Shortly after he arrives, Morris meets the Warden, who remains in office over the course of the entire movie. In reality, Warden Madigan had been replaced by Blackwell in 1961. The Warden character mentions his predecessors Johnston (1934–48) and (incorrectly) Blackwell (1961–63).[11] Blackwell served as Warden of Alcatraz at its most difficult time from 1961 to 1963, when it was facing closure as a decaying prison and financing problems and at the time of the June 1962 escape. He was at that time on vacation at Lake Berryessa in Napa County, California.[12]

The incident in which Doc chops off several fingers with a hatchet was based on an actual incident in 1937. Inmate Rufe Persful, maddened by strict rules that imposed silence on the prisoners, cut off four fingers with a hatchet to try to get transferred off Alcatraz.[13][14]

Production

[edit]Screenplay and filming

[edit]Alcatraz was closed shortly after the true events on which the film was based. Screenwriter Richard Tuggle spent six months researching and writing a screenplay based on the 1963 non-fiction account by J. Campbell Bruce.[15] He went to the Writers Guild and received a list of literary agents who would accept unsolicited manuscripts. He submitted a copy to each, and also to anybody else in the business that he could cajole into reading it.[16]

Everyone rejected it, saying it had poor dialogue and characters, lacked a love interest, and that the public was not interested in prison stories. Tuggle decided to bypass producers and executives and deal directly with filmmakers. He called the agent for director Don Siegel and lied, saying he had met Siegel at a party and the director had expressed interest in reading his script. The agent forwarded the script to Siegel, who read it, liked it, and passed it on to Clint Eastwood.[16]

Eastwood was drawn to the role as ringleader Frank Morris and agreed to star, provided Siegel would direct under the Malpaso banner. Siegel insisted that it be a Don Siegel film and outmanoeuvred Eastwood by purchasing the rights to the film for $100,000.[1] This created a rift between the two friends. Although Siegel eventually agreed for it to be a Malpaso-Siegel production, Siegel went to Paramount Pictures, a rival studio,[15] and never directed an Eastwood picture again.

Although Alcatraz had its own power plant, it was no longer functional, and 15 miles of cable were required to connect the island to San Francisco's electricity. As Siegel and Tuggle worked on the script, the producers paid $500,000 to restore the decaying prison and recreate the cold atmosphere;[1] some interiors had to be recreated in the studio. Many of the improvements were kept intact after the film was made.

Siegel's original ending closed with the guards' discovery of the dummy head in Morris's bed, leaving it uncertain whether the escape attempt had succeeded or failed. Eastwood disliked this and extended the ending by having the Warden searching Angel Island and discovering a chrysanthemum on the rocks, a genus not native to the island but grown on Alcatraz by Doc, and later used by Morris, though it is left unclear if the chrysanthemum was placed there by Morris having survived, or simply washed up when Morris drowned. The Warden is then informed by his aide that he has been summoned to catch the next plane to Washington to face his superiors: it is left up to the viewers to conclude whether or not the escapees succeeded in making their escape.[17]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Escape from Alcatraz was well received by critics and is considered by many as one of the best films of 1979.[18][19][20] Frank Rich of Time described the film as "cool, cinematic grace", while Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic called it "crystalline cinema".[21] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "a first-rate action movie", noting that "Mr. Eastwood fulfills the demands of the role and of the film as probably no other actor could. Is it acting? I don't know, but he's the towering figure in its landscape."[22] Variety called it "one of the finest prison films ever made."[23]

Roger Ebert gave the film 3.5 stars out of 4, writing, "For almost all of its length, 'Escape from Alcatraz' is a taut and toughly wrought portrait of life in a prison. It is also a masterful piece of storytelling, in which the characters say little and the camera explains the action."[24] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune awarded 3 stars out of 4, calling it "very entertaining and well made. The principal problem is a too-quick ending that catches us by surprise."[25] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "A delight for cineastes, 'Escape From Alcatraz' could serve as a textbook example in breathtakingly economical, swift and stylish screen storytelling."[26]

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively reported that 97% of 31 critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 7.1/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Escape from Alcatraz makes brilliant use of the tense claustrophobia of its infamous setting -- as well as its leading man's legendarily flinty resolve."[27] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 76 out of 100 based on nine critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[28]

Box office

[edit]The film grossed $5.3 million in the U.S. during its opening weekend from June 24, 1979, shown on 815 screens. In total, the film grossed an estimated $43 million in the U.S. and Canada based on theatrical rentals of $21.5 million,[7][2] making it the 15th highest-grossing picture of 1979.

Legacy

[edit]In 2001, the American Film Institute nominated this film for AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[29]

Quentin Tarantino called it "both fascinating and exhilarating... cinematically speaking, it's Siegel's most expressive film. "[30]

See also

[edit]- Alcatraz: The Whole Shocking Story

- Alcatraz Island in popular culture

- Six Against the Rock

- Alcatraz Dining Hall

- Survival film, about the film genre, with a list of related films

- The Shawshank Redemption

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Hughes, p.175

- ^ a b c "Box Office Information for Escape from Alcatraz". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 28, 2012.

- ^ "Escape From Alcatraz (1979)". AllMovie.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 22, 1979). "Screen: 'Alcatraz' Opens:With Clint Eastwood". The New York Times.

What Mr. Siegel has made is fiction, a first-rate action movie that is about the need and the decision to take action, as well as the action itself. In this particular case, the action is the escape from "the rock," a maneuver masterminded by a tough con named Frank Morris (Clint Eastwood) with two cronies, Clarence Anglin (Jack Thibeau) and John Anglin (Fred Ward).

- ^ "Escape from Alcatraz (1979)". FilmAffinity.

- ^ Variety film review; June 20, 1979, page 18.

- ^ a b "B.O. from the big house". Variety. October 22, 2001. p. 22.

- ^ a b McFadden, Robert D. (June 9, 2012), "Tale of 3 Inmates Who Vanished From Alcatraz Maintains Intrigue 50 Years Later", The New York Times, New York, NY, retrieved June 9, 2012

- ^ "Investigator Says 1962 Alcatraz Escapees Likely Survived". February 8, 2011.

- ^ "Alcatraz escapee's sister returns to robbery scene". Associated Press. June 19, 2013.

- ^ A History of Alcatraz Island: 1853-2008 by Gregory L. Wellman, published by Arcadia Publishing in June 2008, ISBN 978-0-7385-5815-8

- ^ "Escapes From Alcatraz". SFgenealogy. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Erwin N. "The Rock: A history of Alcatraz Island, 1847–1972". Historic Resource Study. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Sloate 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- ^ a b Litwak, Mark (1986). Reel Power: The Struggle For Influence and Success in the New Hollywood. New York: William Morrow & Company. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0-688-04889-7.

- ^ Hughes, p.152

- ^ "Best Films of 1979". listal.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1979". IMDb.com. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 1979 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: HarperCollins. p. 307. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 22, 1979). "Screen: 'Alcatraz' Opens". The New York Times: C5.

- ^ "Escape From Alcatraz". Variety: 18. June 20, 1979.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 27, 1979). "Escape From Alcatraz". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (June 22, 1979). "Quick ending the only bar to great 'Escape'". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, p. 3.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (June 22, 1979). "'Alcatraz': Other Side of Dirty Harry". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 26.

- ^ "Escape from Alcatraz (1979)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Escape from Alcatraz Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Tarantino, Quentin (December 22, 2019). "Escape from Alcatraz". New Beverly Cinema. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- Sloate, Susan (April 1, 2008). Mysteries Unwrapped: The Secrets of Alcatraz. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-3591-2.

External links

[edit]- 1979 films

- 1979 action films

- Action films based on actual events

- Alcatraz Island in fiction

- American action thriller films

- American prison films

- American docudrama films

- Escapes and escape attempts from Alcatraz

- Films about prison escapes

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films directed by Don Siegel

- Films scored by Jerry Fielding

- Films set in 1962

- Films set on islands

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Malpaso Productions films

- Paramount Pictures films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- English-language action films