Aibonito, Puerto Rico

Aibonito

Municipio Autónomo de Aibonito | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

| |

| Nicknames: "La Ciudad de las Flores", "La Ciudad Fría", "El Jardín de Puerto Rico", "La Nevera De Puerto Rico" | |

| Anthem: "Aibonito" | |

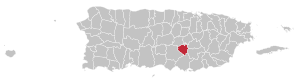

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Aibonito Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°08′24″N 66°15′58″W / 18.14000°N 66.26611°W | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Commonwealth | |

| First settled | 1630 |

| Founded | March 13, 1824 |

| Founded by | Manuel Velázquez |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | William Alicea Pérez (PNP) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 6 – Guayama |

| • Representative dist. | 27 |

| Area | |

• Total | 82 km2 (31.5 sq mi) |

| • Land | 82 km2 (31.5 sq mi) |

| • Water | 0.01 km2 (0.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 731 m (2,401 ft) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 24,837 |

| • Rank | 48th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 300/km2 (790/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Aiboniteños |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00705, 00786 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

| Website | www |

Aibonito (Spanish pronunciation: [ajβoˈnito]) is a small mountain town and municipality in Puerto Rico located in the Sierra de Cayey mountain range, north of Salinas; south of Barranquitas and Comerío; east of Coamo; and west of Cidra, and Cayey. Aibonito is spread over 8 barrios and Aibonito Pueblo (the downtown area and the administrative center of the city). It is part of the San Juan-Caguas-Guaynabo Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Aibonito is located at a relatively high elevation (its main square is the highest in the island at 732 metres (2,401 ft) above sea level), which makes its climate cooler than most of Puerto Rico's towns.

Etymology and nicknames

[edit]The name Aibonito is possibly a combination of Spanish and Taíno from Hatibon or Jatibon, which the native name of the Aibonito River. Jatibon most likely translates to "black river" or "night river", the indigenous name of the river which was later turned into a diminutive in Spanish (Jatibon-ito). It is common to have native place names in Puerto Rico be historically adopted and modified into the Spanish language such as Mucarabones for example, which is a plural of Mucarabon, meaning "owl river" in Taíno.

There's also a legend that tells of a Spanish soldier called Diego Alvarez who on May 17, 1615, reached one of the highest peaks in the area and upon watching the view, exclaimed "¡Ay, qué bonito!" ("Oh, how pretty!") which eventually was turned into the name of the region. If this is the case, it would be considered folk etymology.[2]

Some of the municipality's nicknames include Ciudad de las Flores ("City of Flowers") and Jardín de Puerto Rico ("Puerto Rico's Garden") after the region's floral industry and annual festival, and Ciudad Fría ("Cold City") and Nevera de Puerto Rico ("Puerto Rico's refrigerator") after the fact that the municipality has recorded some of the island's lowest temperatures.[3]

History

[edit]Before the Spanish colonization of the Americas, it is believed that there were Taíno settlements in the region that belonged to Cacique Orocobix domain.

After the Spanish arrived, it is believed that a ranch was established in the region by Pedro Zorascoechea in 1630, which led the development of a hamlet. However, it wasn't until 1822 when Don Manuel Veléz presented himself before the government, representing the inhabitants of the area, to ask for Aibonito to be officially declared a town. This was authorized on March 13, 1824, by Governor Don Miguel de la Torre. The first Catholic church in Aibonito was built in 1825. The building was replaced by the current church, which was started in 1887 and completed in 1897. After the town was officially constituted, barrios started developing in the area.

On the Spanish–American War of 1898, around 800 Spanish and Puerto Rican soldiers were able to defeat the invading American troops due to their strategic placement in Asomante Mountain. This scrimmage came to an end when the Spanish government surrendered on August 12, 1898. The Spanish and Puerto Rican forces at Asomante never surrendered and would have held their position indefinitely if not for the buckling of the Spanish government in Madrid.

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States conducted its first census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Aibonito was 8,596.

Hurricane Maria on September 20, 2017, triggered numerous landslides in Aibonito with the significant amount of rainfall.[4][5][6] Around 1,500 homes were completely or partially destroyed. The hurricane destroyed the poultry industry of Aibonito with nearly 1.8 million chickens killed. Known as "The Garden of Puerto Rico" Aibonito has celebrated a flower festival since 1969. Aibonito's floriculture industry was completely decimated by Hurricane María.[7]

Geography

[edit]Aibonito is located in the Sierra de Cayey, part of the Cordillera Central in Puerto Rico.[8] Aibonito is the town with the highest elevation in Puerto Rico, located at 2,401 feet above sea level. Some of its mountains are La Sierra (2,394 ft), Asomante (2,042 ft) and Buena Vista (2,042 ft).[9]

Barrios

[edit]

Like all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Aibonito is subdivided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located in a small barrio referred to as "el pueblo", near the center of the municipality.[10][11][12][13]

Sectors

[edit]Barrios (which are like minor civil divisions)[14] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[15][16][17]

Special Communities

[edit]Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Aibonito: the Municipal neighborhood, Algarrobo barrio, Amoldadero and Los Muros in La Plata barrio, El Campito, El Coquí, El Fresal, La Españolita, La Represa, Las Bambúas, Los Cuadritos, Parcelas Nuevas in Pasto barrio, Parcelas Rabanal, Parcelas Viejas in Pasto, San Luis, Sector El Nueve, and Sector Gallera.[18]

Water features

[edit]Some of the rivers that flow through Aibonito are the Río de Aibonito, Río Cuyón, Río de la Plata and Río Usabón. Rio Manu

Climate

[edit]Aibonito features a rather mild tropical rainforest climate, owing to its elevation and location, close but still slightly removed from the equator, as well as being directly exposed to the wind and moisture of the Trade Winds. It borders on a subtropical highland climate, and also a humid subtropical climate, though like the former, summers are not much hotter than the warm to cool winters, as it is typical of higher elevations near the equator. As the trade winds coming from the northeast go through orographic lift, rainfall is both greater and more consistent throughout the year than in coastal areas (particularly the south coast only minutes away), with fog being a common occurrence. Aibonito holds the record for the lowest temperature in Puerto Rico. That is 40 °F (4 °C) on March 9, 1911.[19] The highest temperature record is 98 °F (37 °C) recorded on September 29, 1920.[19] Aibonito is among Puerto Rico's coolest towns.

| Climate data for Aibonito (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1906–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 77.3 (25.2) |

77.9 (25.5) |

80.3 (26.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

82.9 (28.3) |

84.3 (29.1) |

84.5 (29.2) |

84.6 (29.2) |

84.6 (29.2) |

83.5 (28.6) |

80.5 (26.9) |

78.1 (25.6) |

86.3 (30.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 73.8 (23.2) |

74.5 (23.6) |

75.8 (24.3) |

77.9 (25.5) |

79.6 (26.4) |

81.4 (27.4) |

81.4 (27.4) |

81.7 (27.6) |

81.2 (27.3) |

79.9 (26.6) |

77.1 (25.1) |

74.7 (23.7) |

78.3 (25.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 67.8 (19.9) |

68.0 (20.0) |

68.8 (20.4) |

70.7 (21.5) |

72.7 (22.6) |

74.4 (23.6) |

74.7 (23.7) |

75.0 (23.9) |

74.7 (23.7) |

73.7 (23.2) |

71.5 (21.9) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 61.9 (16.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

61.7 (16.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

65.8 (18.8) |

67.5 (19.7) |

67.9 (19.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

67.5 (19.7) |

65.9 (18.8) |

63.7 (17.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 57.5 (14.2) |

57.8 (14.3) |

57.8 (14.3) |

59.1 (15.1) |

62.4 (16.9) |

63.8 (17.7) |

64.4 (18.0) |

64.7 (18.2) |

64.3 (17.9) |

63.8 (17.7) |

61.8 (16.6) |

60.0 (15.6) |

55.7 (13.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 43 (6) |

43 (6) |

40 (4) |

45 (7) |

50 (10) |

51 (11) |

55 (13) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

48 (9) |

46 (8) |

47 (8) |

40 (4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.75 (95) |

3.00 (76) |

3.51 (89) |

4.43 (113) |

5.54 (141) |

3.13 (80) |

4.65 (118) |

5.54 (141) |

9.43 (240) |

7.95 (202) |

6.72 (171) |

4.14 (105) |

61.79 (1,569) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 16.4 | 13.7 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 13.7 | 11.3 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 16.6 | 170.9 |

| Source: NOAA[20][21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 8,596 | — | |

| 1910 | 10,815 | 25.8% | |

| 1920 | 13,264 | 22.6% | |

| 1930 | 16,361 | 23.3% | |

| 1940 | 16,819 | 2.8% | |

| 1950 | 18,191 | 8.2% | |

| 1960 | 18,360 | 0.9% | |

| 1970 | 20,044 | 9.2% | |

| 1980 | 22,167 | 10.6% | |

| 1990 | 24,971 | 12.6% | |

| 2000 | 26,493 | 6.1% | |

| 2010 | 25,900 | −2.2% | |

| 2020 | 24,637 | −4.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] 1899 (shown as 1900)[23] 1910-1930[24] 1930-1950[25] 1960-2000[26] 2010[12] 2020[27] | |||

Tourism

[edit]Landmarks and places of interest

[edit]Two of the older landmarks of Aibonito are the Old Encanto Theater, and Moscoso Pharmacy. Their building facades reflect early 20th century architecture. The Mirador Overlook allows for panoramic views of the Plata Valley. The Degetau Stone (in Spanish: La Piedra de Degetau) was where Federico Degetau, a writer, found his inspiration. Casa Museo Federico Degetau is the restored, house museum of the writer. San José Church, which was designed by architect Pedro Cobreros between 1887 and 1897, was built in 1898 is located in the central plaza. There is a plaque commemoration the 100th anniversary of the Spanish–American War at Asomante Memorial, a place with a view of the Central Mountain Range. The Asomante Trench in Spanish: La Trinchera de Asomante is where part of the Spanish–American War took place. The main square is named after Segundo Ruíz Belvis, a national abolitionist hero. The San Cristóbal Canyon, a nine-kilometers-long canyon with waterfalls is located between Aibonito and Barranquitas. In Robles barrio there is an iron bridge with PR-176 and was built in 1892. The annual Festival of Flowers is celebrated each June in Aibonito.[9]

To stimulate local tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico, the Puerto Rico Tourism Company launched the Voy Turistiendo (I'm Touring) campaign in 2021. The campaign featured a passport book with a page for each municipality. The Voy Turisteando Aibonito passport page lists Mirador Piedra Degetau, Casa Museo Federico Degetau, Meyer's Nurseries for agritourism, and several travel routes through Aibonito including the Ruta de Las Flores, Ruta del Pollo, and Ruta Cultural as places of interest.[29]

Culture

[edit]Sports

[edit]Aibonito had a BSN basketball franchise called the Polluelos de Aibonito.[30] In 1986 they beat the defending champions, Atléticos de San Germán, in seven games to win their only championship. In 1987, the Polluelos reached the finals once again, but that time, they lost in seven games to the Titanes de Morovis. Recently, the Polluelos have not been able to see action on the BSN's tournaments because of economic and team ownership problems. Also Aibonito had a Double AA baseball. The franchise is also Polluelos de Aibonito. In 1966 they won their only baseball championship.

Festivals and events

[edit]Aibonito celebrates its patron saint festival in late July or early August. The Fiestas Patronales de Santiago Apostol is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[9] The festival has featured live performances by well-known artists such as Ismael Miranda, and Tommy Torres.[31]

Aibonito celebrates the Aibonito Festival of Flowers between late June and early July.[9][32] During this event, many visitors from other towns and countries come to Aibonito to see a huge display of various flowers and others. Aibonito also celebrates Festival de la Montaña in November.

Economy

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]Aibonito has several plantations of tobacco and coffee. They are also known for their flower plantations. Also, a popular chicken producer in the island, To-Ricos, operates from Aibonito.[9]

Business

[edit]Baxter International has one of its factories located in Aibonito. They produce medical tools for the hospitals and other medical uses.

Industrial

[edit]Other industries located in Aibonito are clothing, furniture and tapestry factories, as well as pottery and ceramics.

Current projects

[edit]In 2014, William Alicea Pérez, the mayor of Aibonito stressed that many improvements had been made to the town and municipality of Aibonito and to its urban center. Several infrastructure projects were completed in 2014, including the inauguration of an assisted living center, and a stadium and he announced future plans for a gym, progress on another stadium and other projects that were under way for the benefit of Aibonito. Pérez indicated that its urban center had been transformed and would continue to be improved upon. The construction of a gym for boxing and martial arts is underway with the help of Miguel Cotto, a Puerto Rican boxing champion.[33]

Government

[edit]All municipalities in Puerto Rico are administered by a mayor, elected every four years. The current mayor of Aibonito is William Alicea Pérez, of the New Progressive Party (PNP). He was first elected at the 2008 general elections.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VI, which is represented by two Senators. In 2024, Rafael Santos Ortiz and Wilmer Reyes Berríos were elected as District Senators.[34]

Transportation

[edit]There are 15 bridges in Aibonito.[35]

Symbols

[edit]The municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[36]

Flag

[edit]The flag of Aibonito features four equal horizontal bands of blue, white, red, and yellow; a green isosceles triangle based on the hoist side bears the town's coat of arms.[37]

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms features a four-paneled shield. The upper left corner features the Asomante Mountain with a sword in front, representing the last battles of the Spanish–American War that took place there. The upper right corner features a white band on a blue field, symbolizing the fog that covers the region in winter. To each side of the band, a purple color flower and a golden lily. The lower left corner features the gold tower of Casa Manresa, to symbolize the spiritual value of the institution. In the lower right corner, a divided green mountain which represents the San Cristóbal Canyon with a seashell above it that symbolizes Apostle James.

Notable people

[edit]- Obie Bermudez, artist

- Rubén Berrios Martínez, politician[38]

- Rafael Pont Flores, journalist[38]

- Eliu Rivera, New Jersey politician

- Ramón Vázquez, baseball player and coach

- Orlando Rosa, 1996 Olympian Freestyle Wrestling

- Christopher Rosario, Connecticut State Representative

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Aibonito". Puerto Rico Me Encanta (in Spanish). 8 January 2021. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Aibonito, Puerto Rico – City Of Flowers". BoricuaOnline.com. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico" (PDF). USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "With Bottles And Buckets, Puerto Ricans Seek The Water To Survive". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. María deshojó a Aibonito y enterró a casi 2 millones de aves" [Maria, a name we will never forget. María tore the leaves off Aibonito and buried nearly 2 million birds]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Aibonito". Discover Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Aibonito Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social, por Rafael Picó. Con la colaboración de Zayda Buitrago de Santiago y Héctor H. Berrios. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Gwillim Law (20 May 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ a b Puerto Rico 2010 - population and housing unit counts (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Map of Aibonito at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (Primera edición ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ a b National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [1] Archived August 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Station: Aibonito 1 S, PR PQ". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department, Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930, 1920, and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities, Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 27 December 1996. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Pasaporte: Voy Turisteando (in Spanish). Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico. 2021. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "El Béisbol Recuerda A Héctor Ferrer". Isla News PR (in Spanish). 6 November 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Fiestas Tradicionales Aibonito, 2013". sondeaquiprnet. El Gobierno Municipal de Aibonito. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Regresa el Festival de las Flores de Aibonito con 32 jardines en exhibición" [Festival of flowers of Aibonito returns with 32 gardens on exhibit]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). 20 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Rinde cuentas el Alcalde de Aibonito". La Cordillera. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ [ https://elecciones2024.ceepur.org/Escrutinio_General_121/index.html#es/default/SENADORES_POR_DISTRITO_Guayama_VI.xml Elecciones Generales 2024: Escrutinio General] Archived 2024-12-30 at elecciones2024.ceepur.org (Error: unknown archive URL) on CEEPUR

- ^ "Aibonito Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "AIBONITO". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Aibonito". Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Mapa de municipios y barrios - Aibonito - Memoria Núm. 43 (PDF). University of Puerto Rico: Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Oficina del Gobernador, Junta de Planificacion, Santurce, Puerto Rico. 1955.

External links

[edit]- "Aibonito from the heights behind the city, Porto Rico". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 November 2019.